Storyboards with Stephen DeStefano at MoCCA

One by one, the folding chairs set up in New York City’s Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art are being occupied. It’s the first evening of a three-night course in storyboarding – part of MoCCA’s ongoing educational program – and the dozen or so folks filling those chairs are here to learn from Stephen DeStefano.

Stephen, whom MoCCA Senior VP of Education Danny Fingeroth refers to as “the guru of storyboarding” has been doing boards for quite a while. Back in 1992 he made the jump from comics (where he created Mazing Man for DC) and into the field when he got a call from his buddy Bill Wray, who was boarding for Ren and Stimpy at the time. Encouraged by Wray, Stephen moved to L.A. later that year and broke into the business drawing backgrounds and doing layouts. “That’s the way to learn – no one can enter the field off the bat as ‘board artist,” he cautions. “It’s a good introduction and gives you a chance to work your way up.”

Stephen, whom MoCCA Senior VP of Education Danny Fingeroth refers to as “the guru of storyboarding” has been doing boards for quite a while. Back in 1992 he made the jump from comics (where he created Mazing Man for DC) and into the field when he got a call from his buddy Bill Wray, who was boarding for Ren and Stimpy at the time. Encouraged by Wray, Stephen moved to L.A. later that year and broke into the business drawing backgrounds and doing layouts. “That’s the way to learn – no one can enter the field off the bat as ‘board artist,” he cautions. “It’s a good introduction and gives you a chance to work your way up.”

Stephen’s MoCCA students are looking for a leg up in the craft, or are simply curious about the nuts and bolts of an animation fundamental. CGI animators, comic book artists and even a handful of School of Visual Arts instructors (not to mention one AWN writer) have come to try their hand at boarding.

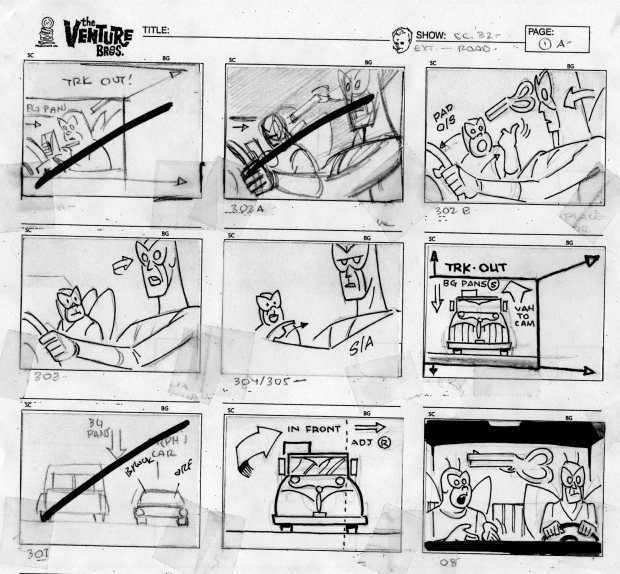

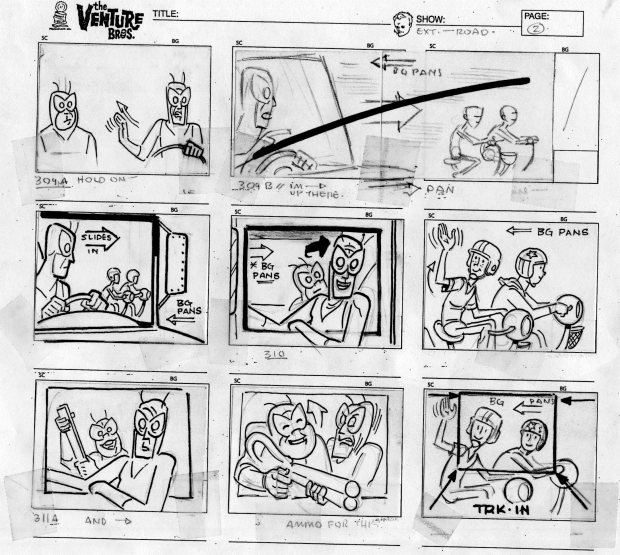

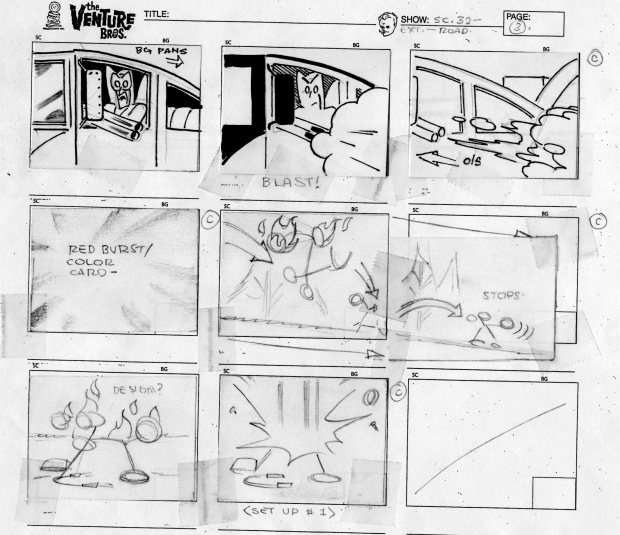

Stephen explains technical aspects of boarding that have always mystified this writer: how to indicate pans and zooms within or outside individual panels, or turning pages sideways if necessary to depict extended vertical camera moves that could never fit into a single panel. Put simply, a storyboard artist should never feel constrained by the borders of the empty panels staring at him from a formatted page.

As might be expected, the class produces a variety of approaches to the same material. In the superhero story the differences are essentially in visualizing the action described in the script, but the comedy storyboards widely vary, with each student coming up with gags representing their own sensibility as much as the premise they began with. Stephen is an appreciative audience, praising his students’ imagination and offering nuts-and-bolts technical advice as necessary. (“The first drawing of every new scene should be on model – you can take it easy after that…your camera jumps around a lot; the more you move your camera the more confused the viewer will be…

Stephen outlines the two very different shows an artist generally boards: broad comedy outlines and precisely written superhero action scripts. In the first according to Stephen, the board artist is practically a writer/cinematographer/actor, thinking up visual gags to hang onto the outline. By contrast, superhero scripts challenge the artist to keep stretches of dialog visually interesting while making sure action scenes are both dynamic and easy to follow. Either way, he says, “great boards show you something you don’t expect.”

Flip a coin and take your choice: Stephen presents a brief comedy outline and a few pages of a superhero script and challenges the class to board out their choice. Regardless of subject matter, the sequence remains the same: begin with ‘thumbnail’ frames (1¼ by 2 ¼ inch), follow with larger ‘roughs’ (approximately 6½ by 3½ inch) and end with cleaned up and fully rendered final boards.

Over the three class sessions Stephen gives advice, critiques his students’ ongoing boards and shares his impressions of other animators and storyboarders. (“Jackson Publick is one of the two or three best storyboard artists I ever met – his boards look like Stanley Kubrick’s… storyboard artists hate writers telling us what to do [when their scripts describe camera angles]…[top-notch] storyboard artists are like rock stars: they come in late, goof off – and are sought after”) At one point Stephen offers a seemingly counter-intuitive observation of the craft: “some of the best storyboards I’ve seen were stick figures because they ‘read’ clearly – you’re not necessarily here to draw beautifully.”

At the end of the three nights the students are ready to finalize their boards and Email them to Stephen for post-class review and feedback. (His first warning: “producers expect final boards to be animation-ready.”) The feedback from his students is 100% thumbs up, with one enthusing “having wrestled with these problems, it’s great to see how a pro can actually solve them… all the graphic tricks you employ to make complicated actions clear are inspiring. Thanks for sharing these, now that I’m primed to take it in.”

Fingeroth shares that student’s sentiments. “Though Stephen had never taught before, the minute I met him I knew he was a natural at teaching–his talent and enthusiasm for his subject are obvious, and I was eager to make him part of the MoCCA team.”

The feeling is no doubt mutual; if anything, Stephen enjoys being part of a team. “I like to create by myself [when working in comics] – but I don’t always like that. Animation pays relatively well and you work with nice people you’re part of a community.

“Animation people are a very fun kind of people. We all have our neuroses because we watch cartoons and we want to be around other people. It’s mostly a joy working in animation.”

— Joe Strike

[AWN.com]